Ideas for Students as Partners

What Student as Partners (SaP) activities look like in practice can vary considerably, and examples will demonstrate a wide range of activities. This article points to a number of case studies featuring a variety of partnerships and collaborations between students and staff.

Why?

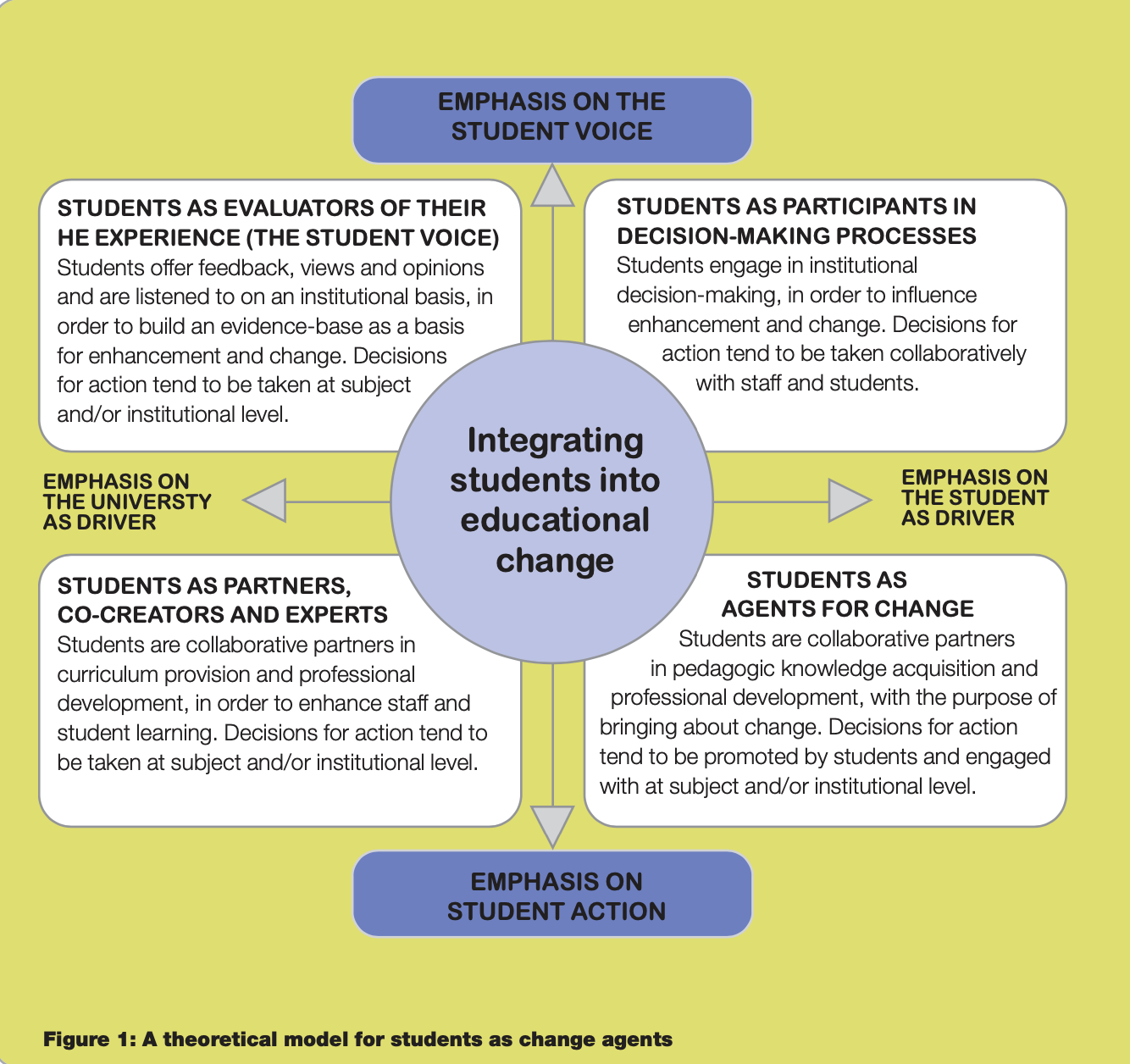

The notion of SaP in learning and teaching can be viewed as quite radical. For many, it requires stepping out of a more traditional understanding of the role of the academic, which in itself can be challenging. The following diagram (Dunne & Zanstra, 2011, p. 17) may be helpful in clarifying the differences between 'student voice' and 'students as partners' (refer also to the What is Students as Partners? article for associated information).

Figure 1: A theoretical model from Dunne & Zanstra (2011, p. 17)

Figure 1: A theoretical model from Dunne & Zanstra (2011, p. 17)

Top right-hand quadrant: when student voice and student as driver are emphasised, students are participants in decision-making processes at the institutional level and actions are taken in collaboration with staff.

Lower right-hand quadrant: when student action and student as driver are emphasised students are agents for change, with decisions for action promoted by students and engaged with at subject and/or institutional level.

Top left-hand quadrant: when student voice and university as driver are emphasised students are evaluators of their higher education experience which may inform decisions taken at subject and/or institutional level.

Lower left-hand quadrant: when university as driver and student action are emphasised students are partners, co-creators and experts in curriculum provision and professional development. Decisions for action tend to be at subject and/or institutional level.

Case Studies

Seeing how others have approached SaP activities can help alleviate concerns or uncertainties. Case studies 2-5 were sourced from Healey and Healey (2021).

A specific goal of the Students as Partners in Mentoring (SaPiM) project was to develop strategies for preparing and supporting students entering higher education. The student-staff partnership focused on increased support for first-year students unfamiliar with the academic, social and cultural functioning of tertiary education. A first-year student mentoring program was developed in the School of Education from the ground-up utilising a student-staff committee, which oversaw the development of a Student Partnership Agreement as well as the overall implementation of the program. A research project that ran alongside the SaPiM program explored the reflections of project participants (mentors, mentees, committee members) involved in either the design and development or implementation of SaPiM (see O’Shea et al. 2017, 2021). Based on a series of discussions within the student-staff committee, it was decided to develop a mentoring program that would target first-year student transition to university. Particular focus was on recruiting experienced education students as mentors across a range of educational degrees (Early Years Education, Primary Education, Health and Physical Education, Science Education Mathematics Education, Masters of Teaching) from a diverse range of backgrounds and experiences, for example, single mothers, international students, students living on campus. Mentors were encouraged to draw on their own authentic learning experiences when providing advice and support to beginning students. They undertook training which included information about services on campus, access to a Moodle site (constructed by students) for relevant resources and information about mental health and well-being. After the pilot in 2017, these mentors became Super-Mentors who took on leadership roles in recruiting, training new mentors, social events etc. The program is recognised by UOWx so student participation will be noted on their testamur.

First-year students (in classes ranging from 50 to 350) come up with a researchable question, conduct a discipline-relevant investigation, and share their findings. The fields of research are diverse: business statistics, environmental studies, astronomy, animal bioscience, kinesiology, geography, history, and academic skills classes. Projects can consist of an assignment spanning a minimum of three weeks or be fully integrated across a curriculum. With the guidance of experienced students who work as research coaches, first years learn from content experts or examine existing, emerging, or historical data and artifacts to explore topics of interest to them. Sample research questions might be, “Can the Zika virus-carrying mosquito survive in the current Toronto, Canada climate?”, “Are class members who reside in rural areas more physically active than those who reside in urban centres?”, “How many years would it take to recuperate energy savings equivalent to the start-up costs of installing solar panels in an average, local residence?” Students may work in groups of four to twelve to develop research questions of interest to them which are answered by class members through online surveys. They may examine issues in the media such as popular film, world events, or controversial topics. The data from questionnaires or other primary sources lead to students’ conducting literature reviews and synthesising and evaluating results. To communicate findings, students create research posters, develop web pages, deliver in-class presentations, or otherwise engage in exchanging ideas and reflecting on what they have learnt throughout their class-based research experience.

A partnership arose between Birmingham City University and Birmingham City Students’ Union that aimed to create a greater sense of learning community at the university. Through the integration of students into the teaching and pedagogic research communities of the University, the focus was to enhance the student learning experience. Over the past ten years, this drive has seen the employment of over 1500 students and the participation of 500 staff in 700 funded projects. Staff and students are invited to propose educational development projects in which students can work in an academic employment setting in a paid post at the University. Students negotiate their own roles with academic/professional staff and are paid for up to 100 hours of work. Each project is designed to develop a specific aspect of learning and teaching practice. Typically, these may result in new learning resources, developments in curriculum design or the evaluation of innovations and changes that have already been made. It is key to the scheme that students are employed as partners not assistants, co-creators not passive recipients of the learning experience.

As part of Macquarie University’s plan of international work-integrated and community-based service-learning placements through its Professional and Community Engagement (PACE) program, students and workplace partners have been involved in co-creating curricula. The first activity involved eleven community-based organisations from seven countries. Students were involved in this project to a limited extent, working with workplace partners at a co-creation workshop, trialling activities and contributing to a series of videos focused on providing advice to students. The second activity was the on-going co-creation of a unit (10 iterations, 2 times per year, 2014–2019) that supports third year undergraduate students undertaking international WIL (work-integrated learning) placements. The student cohort came from multiple disciplinary backgrounds, ranging from business to health sciences. Students contributed to co-creation both in their placements and in the classroom, through face-to-face workshops, online discussion forums and assessment tasks. Through co-creation, workplace partners benefit from having a voice in preparing students to participate meaningfully in their organisations. Workplace partners, students and university staff play similar roles in their contribution to co-creation; as planners, contributors, creators and reviewers.

CIN is a student-led initiative that provides a seamless pathway for CIN students through the whole which equips them with the skills and connections that are essential for success in the real world. CIN partners with Bachelor of Creative Industries (BCI) and collaborates with academics to create opportunities for students, staff and industry to engage with one another. Students, staff and industry work together collaboratively on projects in open and dynamic loops that go far beyond surveys and traditional feedback mechanisms. CIN began as the BCI Champions peer mentoring program that was co-designed between students and staff with the aim of building community within the first year BCI cohort. Six months in, the BCI Champions took the initiative and pitched an idea to the Program Convener and Dean of the Faculty to take on a broader remit and establish a professional organisation - CIN. They wanted to run initiatives across both curricular and co-curricular engagement with students, teachers and industry. The model that the students proposed drew heavily upon their BCI learning experiences and presented an authentic and dynamic way to enhance their educational experience. They wanted to be able to engage with the practices of collaboration, career management, networked learning, transdisciplinarity, and enterprise (‘21st century skills’), all of which are emphasised in the BCI curriculum. Through curricular and co-curricular initiatives, students build their capacities as future graduates, whilst simultaneously enriching curriculum, staff, students and the broader university environment.

Other initiatives run by CIN include: co-design of BCI curriculum; Orientation Program; Coterie and Creative Enterprise Australia (industry partnership); People, Industry & Peers (PIP) networking events; Capacity building staff / students around students as partners; social media campaigns; and Work Integrated Learning Workshop and the Industry Q and A events.

Related information

- International Journal for Students as Partners (open source) | External resource

- ESCalate, University of Exeter’s Student as Partners Change Agents project | External resource

References

Bilous, R., Hammersley, L., Lloyd, K., Rawlings-Sanaei, F., Downey, G., Amigo, M., Gilchrist S. & Baker, M. (2018). ‘All of us together in a blurred space’: principles for co-creating curriculum with international partners, International Journal for Academic Development, 23(3), 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1412973

Dunne, E., & Zandstra, R. (2011). Students as change agents–new ways of engaging with learning and teaching in higher education. ESCalate Higher Education Academy Subject Centre for Education, University of Bristol. http://escalate.ac.uk/8064

Healey, M. & Healey, R. (2021). Students as partners and change agents, handout. Healey HE Consultants. https://www.healeyheconsultants.co.uk/resources

O’Shea, S., Bennett, S., Delahunty, J. (2017). Engaging ‘students as partners’ in the design and development of a peer-mentoring program. Student Success, 8(2), 113-116. https://studentsuccessjournal.org/article/view/390

O’Shea, S., Delahunty, J., & Gigliotti, A. (2021). Creating Collaborative Spaces: Applying a “Students as Partner” Approach to University Peer Mentoring Programs. In H. Huijser, M. Kek, & F. F. Padró (Eds.), Student Support Services. (pp. 1–20). Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3364-4_7-1

Ruskin, J & Bilous, R.H. (2020). A tripartite framework for extending university-student co-creation to include workplace partners in the work-integrated learning context, Higher Education Research & Development. 39(4), 806-820. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1693519