Constructive alignment

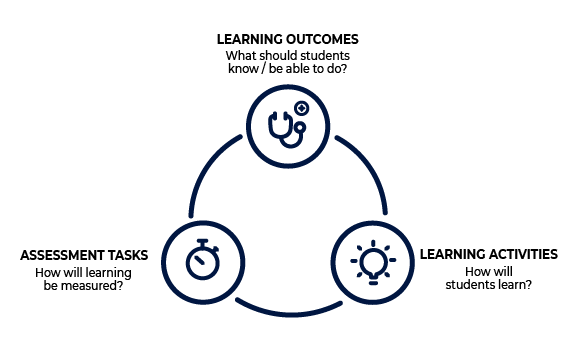

Constructive alignment puts the emphasis on what learners do within the context of a learning event to construct knowledge, skills and experiences. For learners to be able to construct meaning, teaching teams need to make deliberate synergies between the following three, interrelated components of constructive alignment:

- Learning outcomes: A collection of measurable goals for learners.

- Assessments: Tasks that occur before, during or after learning events that will best evidence learners’ progress towards achieving learning outcomes.

- Content: Information and activities that cultivate the knowledge, skills, experiences and attitudes learners’ need to evidence/demonstrate learning outcomes.

Why?

Advanced by John B. Biggs for university contexts, constructive alignment recognises that "knowledge is constructed by the activities of the learner" (Biggs, 2014, p. 9) rather than via teacher-to-learner knowledge transmission. Constructive alignment encourages teachers to focus on the what and how of learning rather than predetermined topics. When constructive alignment is effectively implemented it increases the quality of learning events and experiences.

How?

Learning outcomes: What should students know/be able to do?

Assessment tasks: How will learning be measured?

Learning activities: How will students learn?

- Develop a collection of learning outcomes that best represent the goals of the learning event and any overarching goals (e.g., course-wide outcomes).

- Design authentic and appropriate assessment tasks that enable learners to evidence learning outcomes.

- Utilise purposeful content and activities that are intentionally selected to give learners the best opportunity to develop the knowledge, skills and experiences needed to complete assessment tasks and evidence selected learning outcomes.

Step one:

Teaching teams start by determining the knowledge, skills, experiences and attitudes learners should have by the end of a learning event (e.g., subject), as aligned to its place in any broader learning experiences (e.g., a course). Stakeholders (e.g., university staff, industry) and students can be included in this process, and their associated data synthesised/used to inform learning outcome development. Bloom’s taxonomy is one example of a taxonomy with an associated collection of measurable verbs that can be used to write learning outcomes and inform the selection of aligned and appropriate assessment tasks.

Step two:

Once a list of learning outcomes has been drafted, assessment tasks can be designed. Assessments need to be authentic and appropriate in both content, method and product to effectively provide evidence of learners’ progress toward achieving the learning outcome(s). When designing an assessment task, revisit the measurable verb you have selected. Consider if this verb allows the desired learning to be adequately captured, or if an alternative verb would provide better alignment. Alternative verbs can be identified using Bloom’s Taxonomy. It is important to finalise learning outcomes and assessment tasks before submitting learning event documentation such as proposals.

Step three:

After completing steps one and two, it is time to intentionally select the sequence of information, activities and experiences that will best support learners throughout their learning event. The intentional sequence of content formats and activities should allow for learner diversity and be sequenced in a way that builds in complexity.

For example:

| Intended Learning Outcomes: What Students Learn |

Ways of Learning: Origins and Theory |

Common Methods: What the Teacher Facilitates |

| Building skills Physical and procedural skills where accuracy, precision and efficiency are important |

Behavioural learning Behavioural psychology; operant conditioning |

Tasks and procedures Practice exercises |

| Acquiring knowledge Basic information, concepts and terminology in a discipline or field of study |

Cognitive learning Cognitive psychology, attention, information processing, memory |

Presentations Explanations |

| Developing critical, creative, and dialogical thinking Improved thinking and reasoning processes |

Learning through inquiry Logic, critical, and creative thinking theory, classical philosophy |

Question-driven inquiries Discussions |

| Cultivating problem-solving and decision-making abilities Mental strategies for finding solutions and making choices |

Learning with mental models Gestalt psychology, problem-solving, and decision theory |

Problems Case studies Labs Projects |

| Exploring attitudes, feelings and perspectives Awareness of attitudes, biases, and other perspectives; ability to collaborate |

Learning through groups and teams Human communication theory; group counselling theory |

Group activities Team project |

| Practising professional judgement Sound judgement and appropriate professional action in complex, context-dependent situations |

Learning through visual realities Psychodrama, sociodrama, gaming theory |

Role playing Simulations Dramatic scenarios Games |

| Reflecting on experience Self-discovery and personal growth from real-world experience |

Experimental learning Experimental learning, cognitive neuroscience, constructivism |

Internships Service-learning Study abroad |

Adapted from Davis, J.R. & Arend, B.D. (2013). Facilitating seven ways of learning: A resource for more purposeful, effective and enjoyable college teaching. Sterling Virginia: Stylus, p.38.

References

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5-22.

Biggs, J.B. & Tang, C. S. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university : What the student does (4th edition.). McGraw-Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education.

Biggs, J., (2011). Constructive alignment. Johnbiggs.com. https://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/constructive-alignment/

Harvard University (n.d.). Taxonomies of learning. The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, Harvard University. https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/taxonomies-learning